When gold was discovered in Coloma on January 24, 1848, it kicked off one of the largest mass migrations in history. As news of the discovery spread, people from all around the world headed to California. More than 100,000 people would come to California within the first year of discovery. The majority of those headed to California were Americans, but gold seekers also came from Europe, Asia, South and Central America, Australia, and New Zealand. Roughly half of those destined for the gold fields traveled by land, while the rest traveled by sea.

Many came with the dream of quickly striking it rich and then returning home. The reality of life in the gold fields would end that dream. Mining gold was hard, backbreaking work, with no guarantee of getting rich.

Sutter’s Mill, 1851

This image, a photographic reproduction of a painting by Arthur Nahl, depicts John Sutter’s Coloma sawmill as it appeared in 1851, a few years after the gold discovery. John Sutter was a Swiss immigrant who established Sutter’s Fort in Sacramento before building the sawmill approximately 40 miles away, relying primarily on forced labor from California’s native peoples.

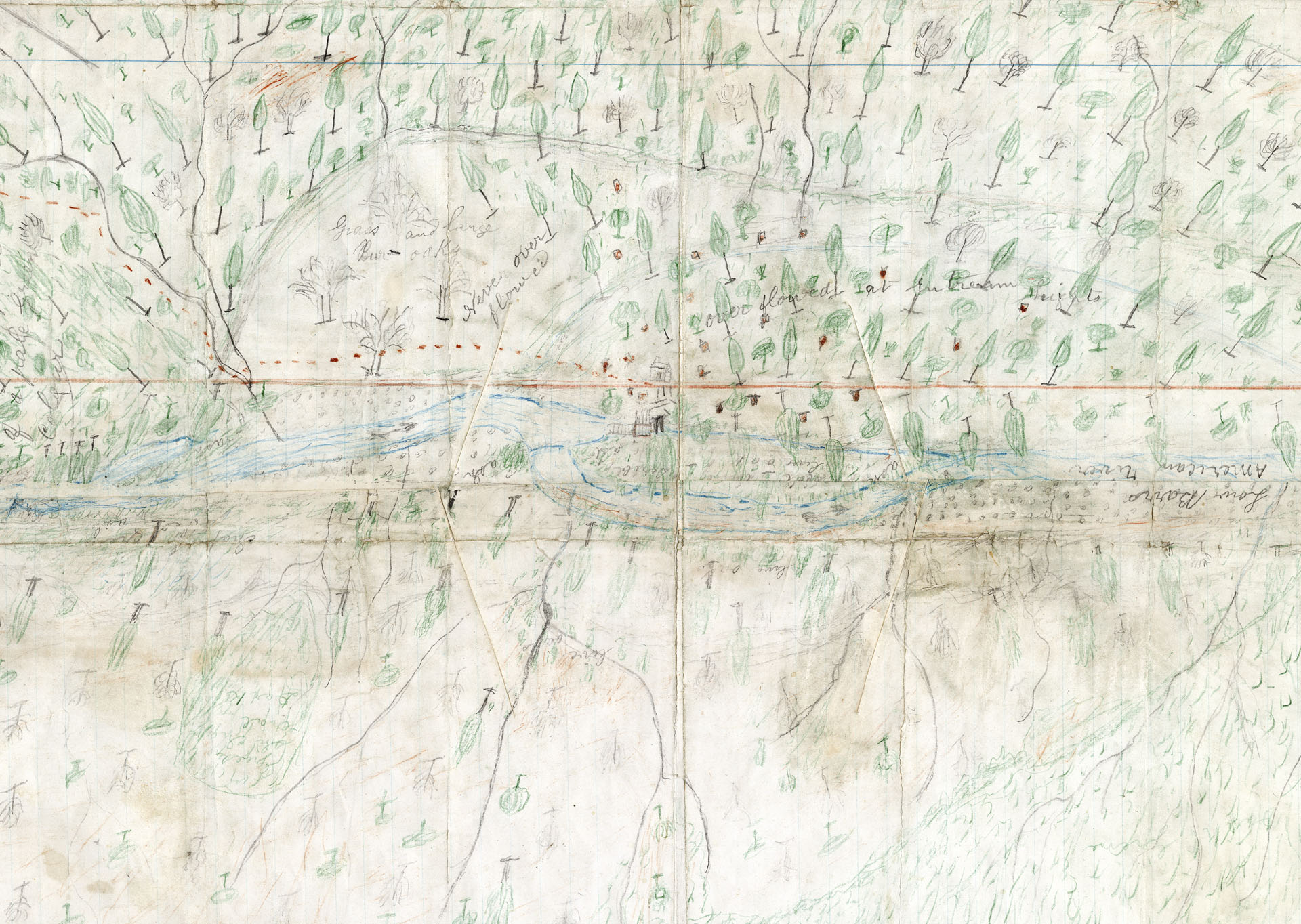

Drawing of Coloma Valley

James W. Marshall discovered gold on January 24, 1848. This image shows a map he sketched depicting the Coloma Valley and includes the south fork of the American River. This map, along with two drawings of the gold discovery, were found in a desk at his cabin in Kelsey (near Placerville) after his death. John Sipp, who purchased the cabin at an administrator’s sale, gave these to the State Library in 1910.

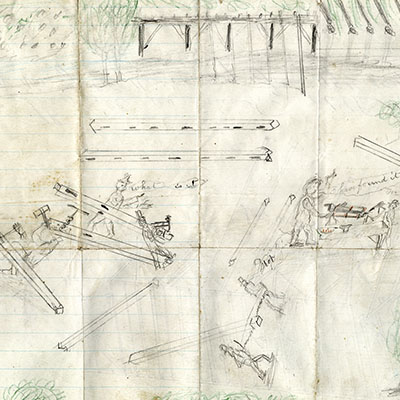

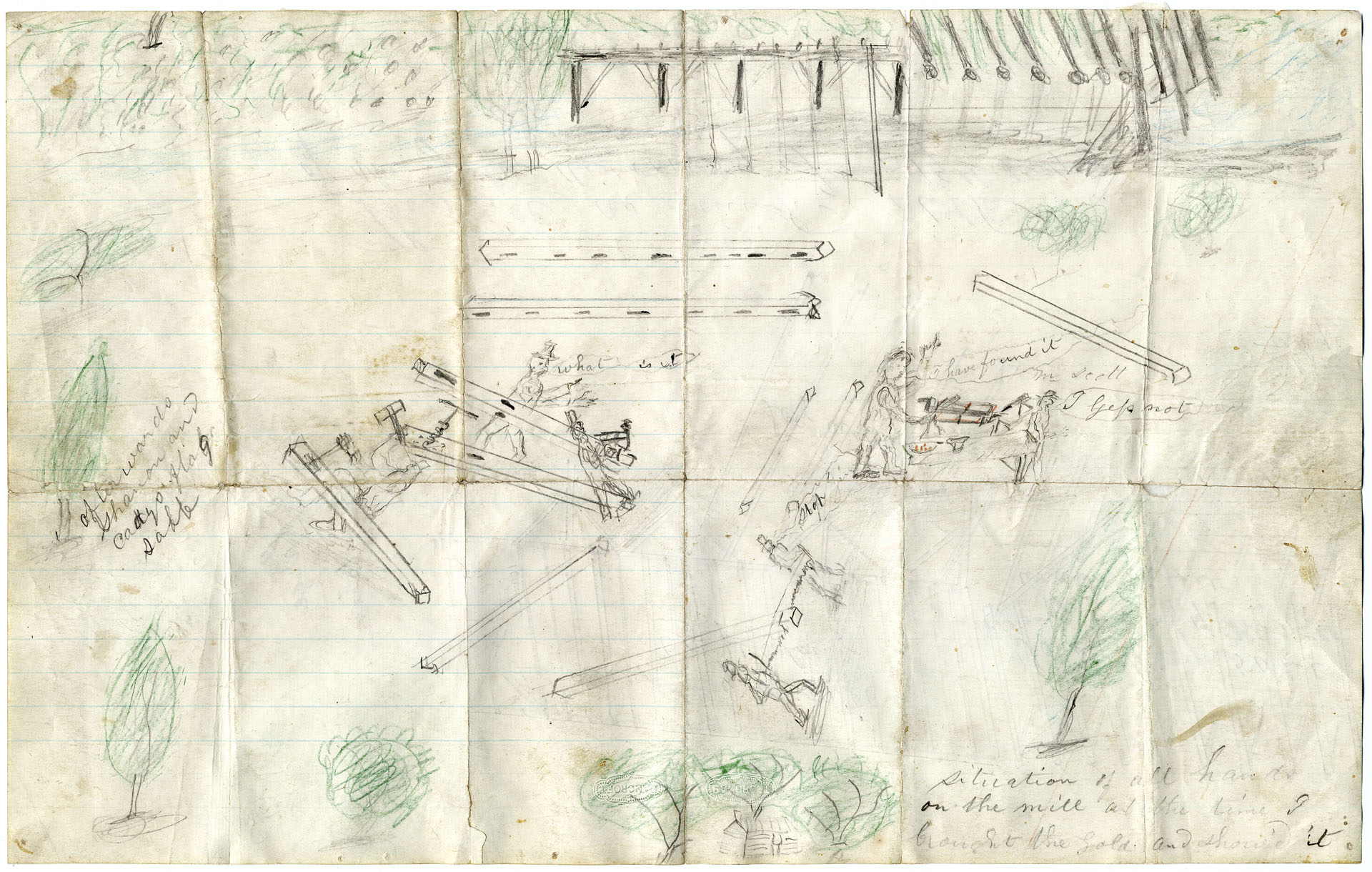

Marshall’s drawing of gold discovery

One side of James W. Marshall’s double-sided drawing of Sutter’s Mill showing the gold discovery. The drawing depicts the men sawing and hammering logs, while text bubbles are used to record their initial skepticism when Marshall announced, “I have found it.”

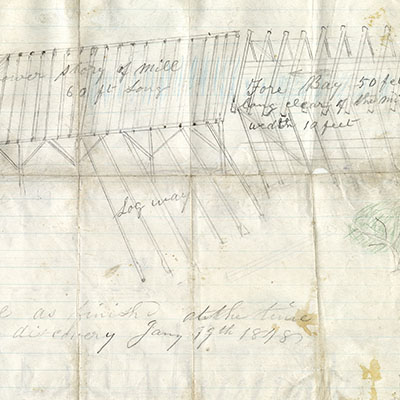

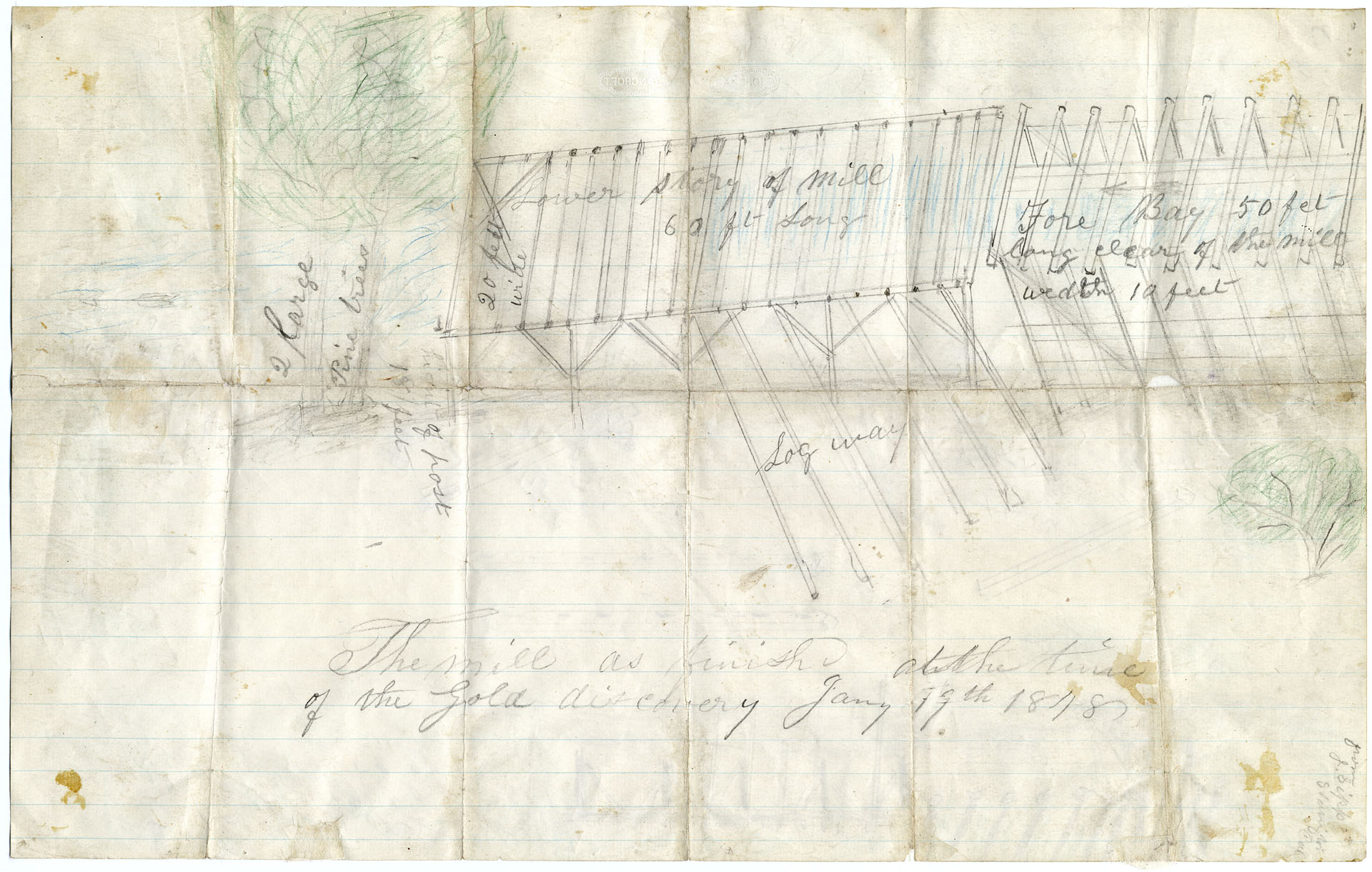

Marshall’s drawing of Sutter’s Mill

The second side of James W. Marshall’s double-sided drawing of Sutter’s Mill shows the completed sawmill, including dimensions. Marshall wrote the following caption: “The mill as finished at the time of the gold discovery Jany. 19th 1848.” Marshall confused the actual date of the discovery and hence the date of the 19th rather than the 24th.

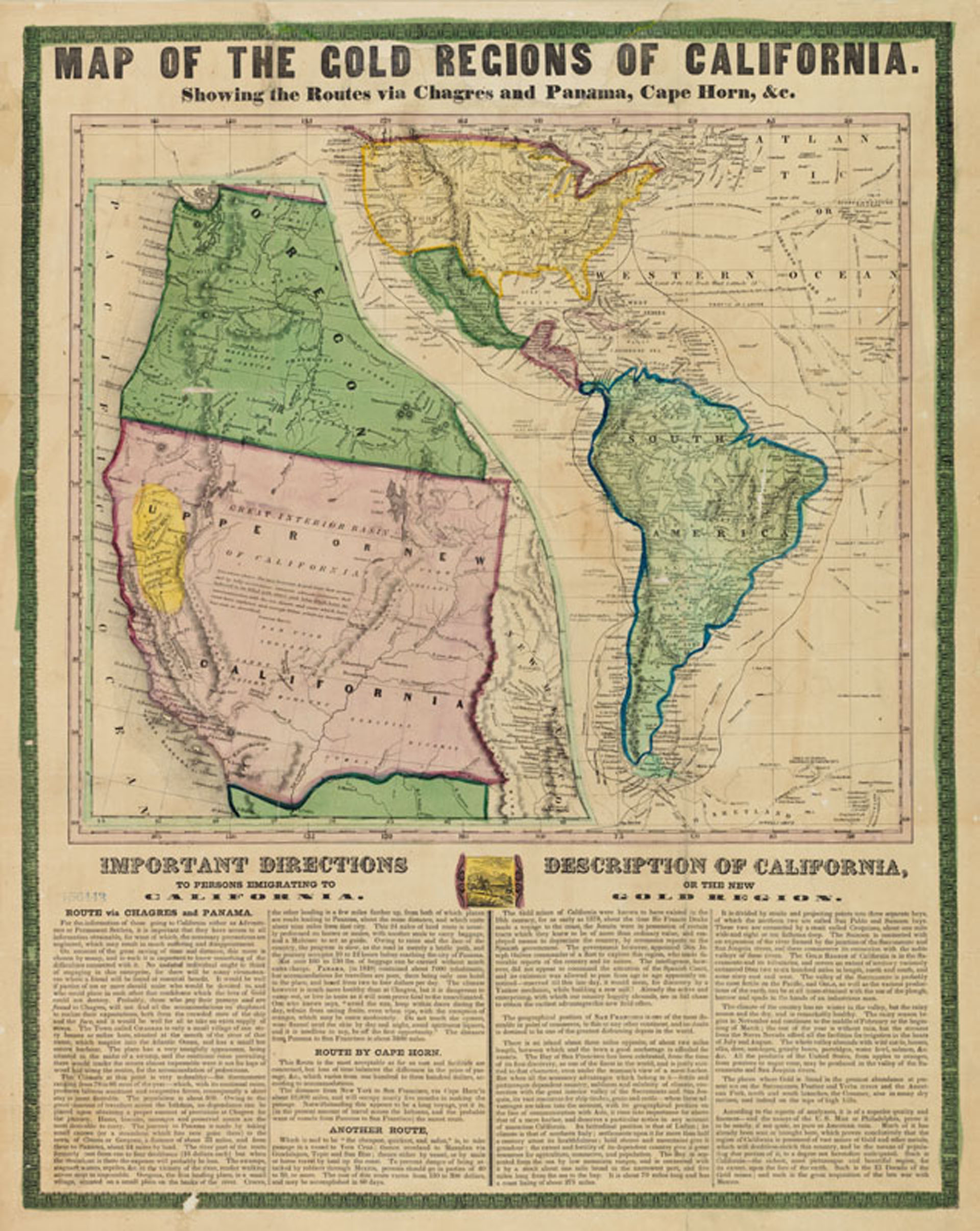

Map of the Gold Regions of California, 1849

This map depicts travel routes to California; the gold region is tinted in yellow. The majority of those headed to California were Americans, but gold seekers also came from Europe, Asia, South and Central America, Australia, and New Zealand. The journey by sea was challenging. Passengers were at risk of shipwreck, spoiled rations, and disease brought on by crowded and unsanitary living quarters.

The Independent Gold-Hunter, 1850

The gold mania of 1848 and 1849 inspired a number of satirical cartoons, such as this print. In reality, the journey overland to California through the continental United States was difficult and travelers faced hardships like disease, inclement weather, challenging terrain, lack of supplies, and inadequate food sources for their animals.

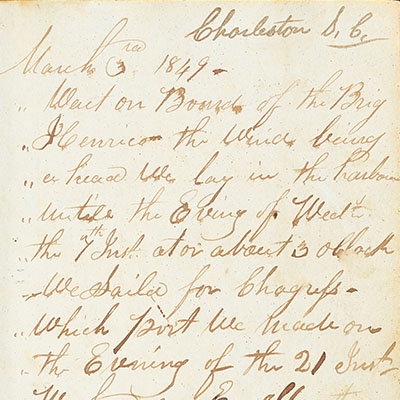

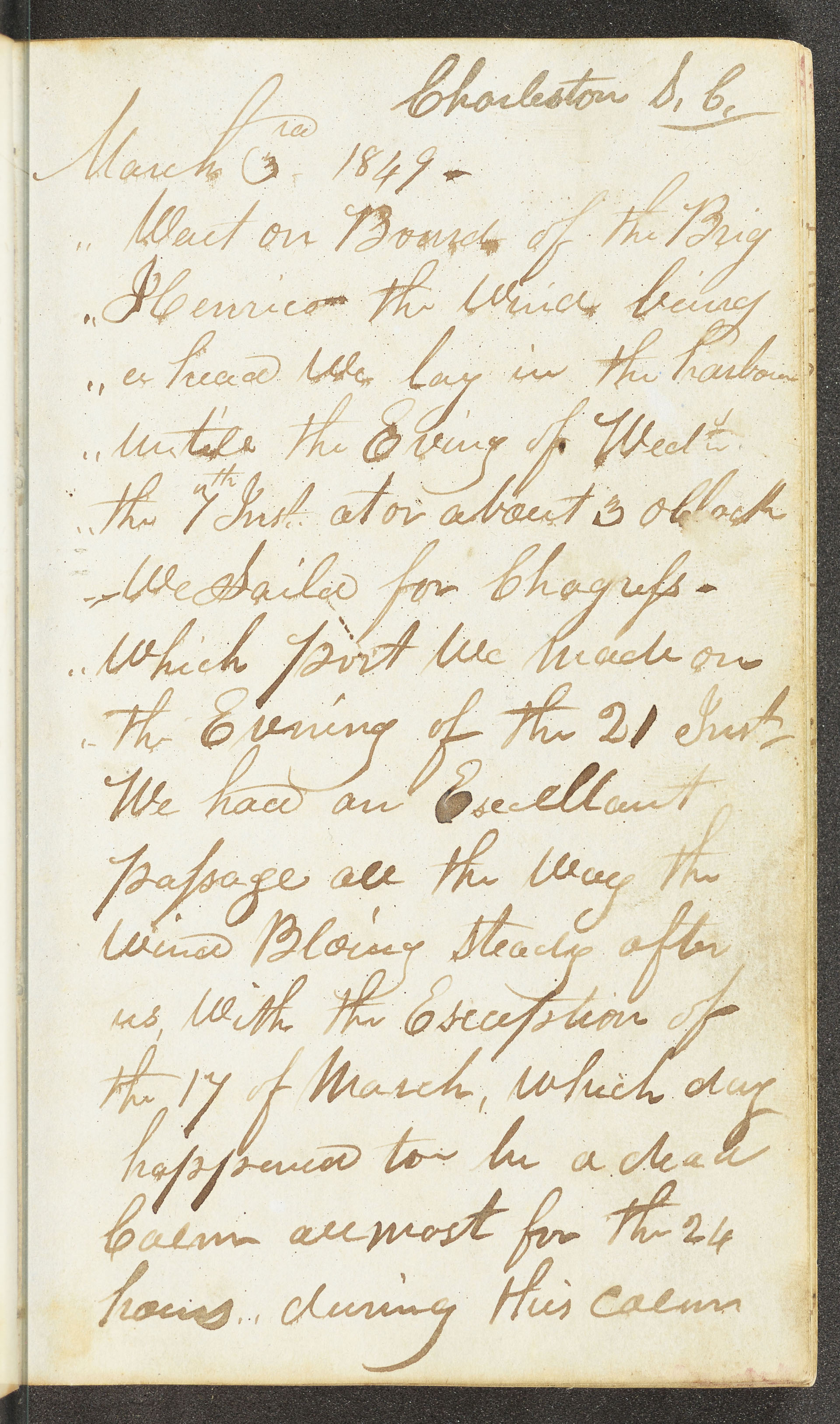

Palmetto Mining Journal

This pocket-size journal is a record kept by a member of one of the many mining companies that set out for California in the spring of 1849. The Palmetto Mining company sailed from Charleston to San Francisco on a ship named Henrico. This volume belonged to an Edward Keegan of South Carolina, but according to his daughter, he did not write the journal. The unknown writer chronicled the activities of the company on the ship and later as they hunted for gold near Coloma. The journal also describes encounters with California indigenous people at the local rancherias.

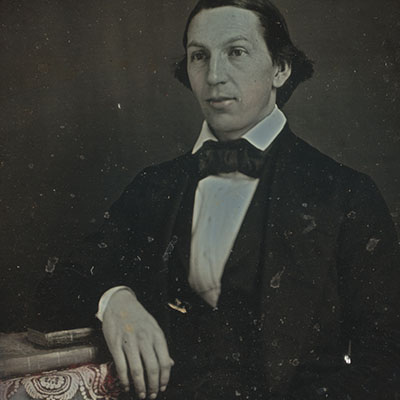

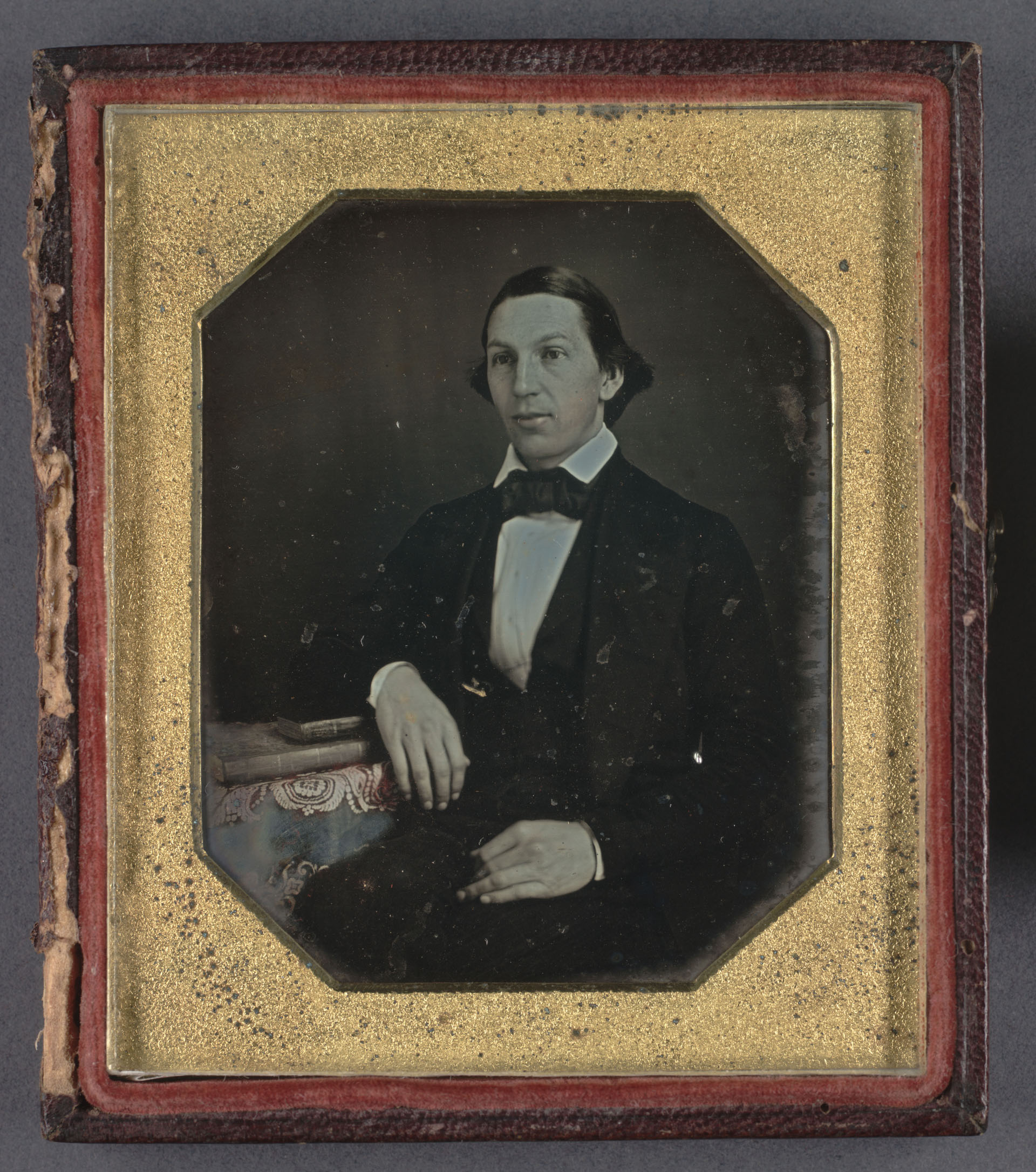

Daguerreotype of Joseph Benton

Reverend Joseph A. Benton was one of many who caught “gold fever” and headed west. On his way to California aboard the Edward Everett he preached to the passengers. Benton wrote: “The world’s centre will have changed, and no man will be thought to have seen the world till he has visited California.” He established the First Congregational Church in Sacramento in 1851, then moved to San Francisco in 1864 and was pastor of a church there, was professor of Biblical Literature at the Pacific Theological Seminary, was a founding trustee of what became the University of California and was elected to the California State Senate in 1863.

Wonderful Facts from the Gold Regions

This 1849 publication was one of many guidebooks published for those headed to the gold fields. Unlike many other accounts that romanticized the ease of striking it rich, author Daniel Walton cautioned readers about the lure of California, writing: “Our opinion is, that there is a great deal of knavery in getting up this gold fever.”

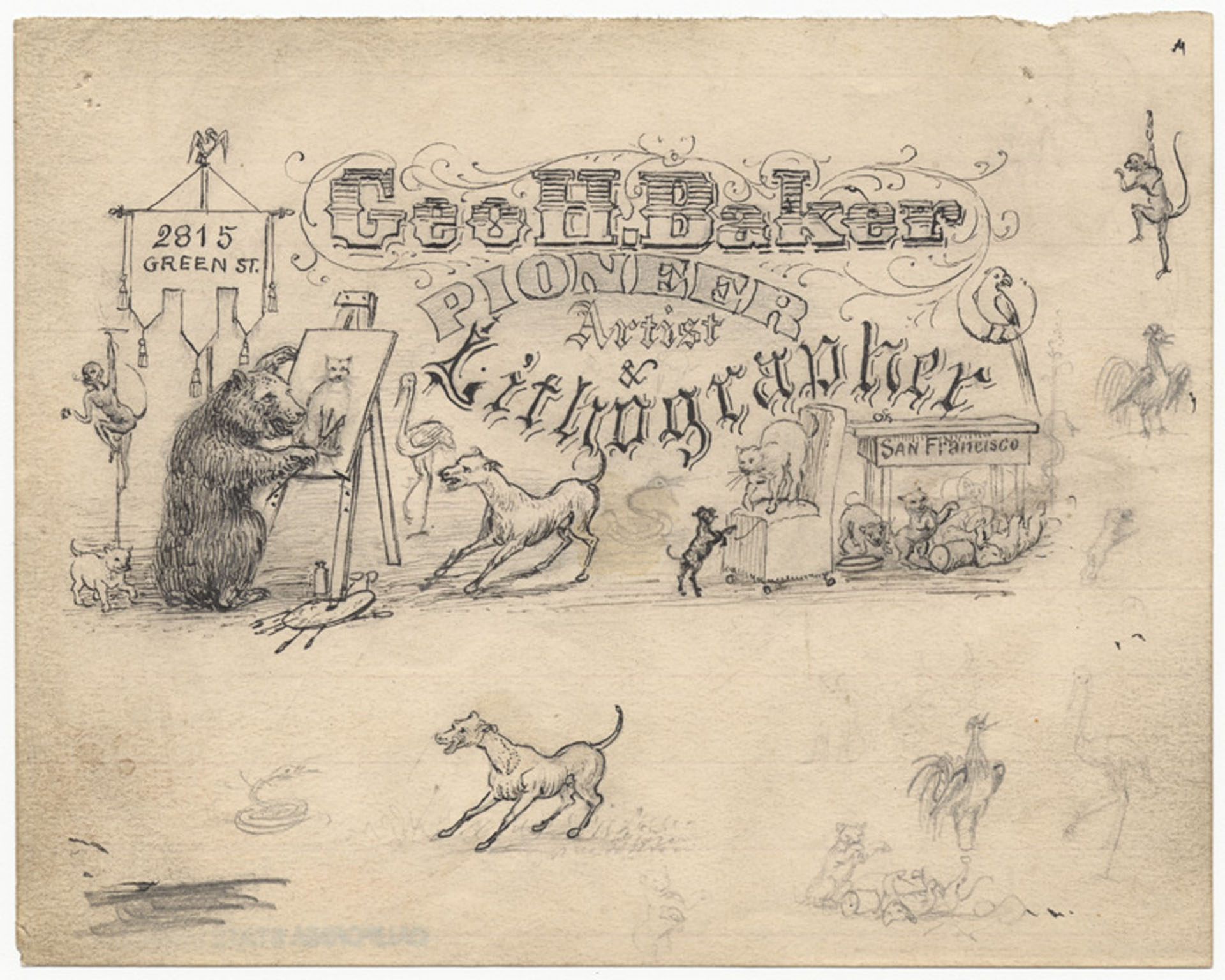

George H. Baker Pioneer Artist

Many who came to California to mine gold ended up working in new professions or pursuing their previous occupations. George Holbrook Baker was an artist, publisher, and lithographer in New York when he caught “gold fever” and joined the rush to California in 1849. After a brief stint in mining, Baker returned to his previous profession. He continued to publish and create illustrations that were some of the earliest published depictions of the state.

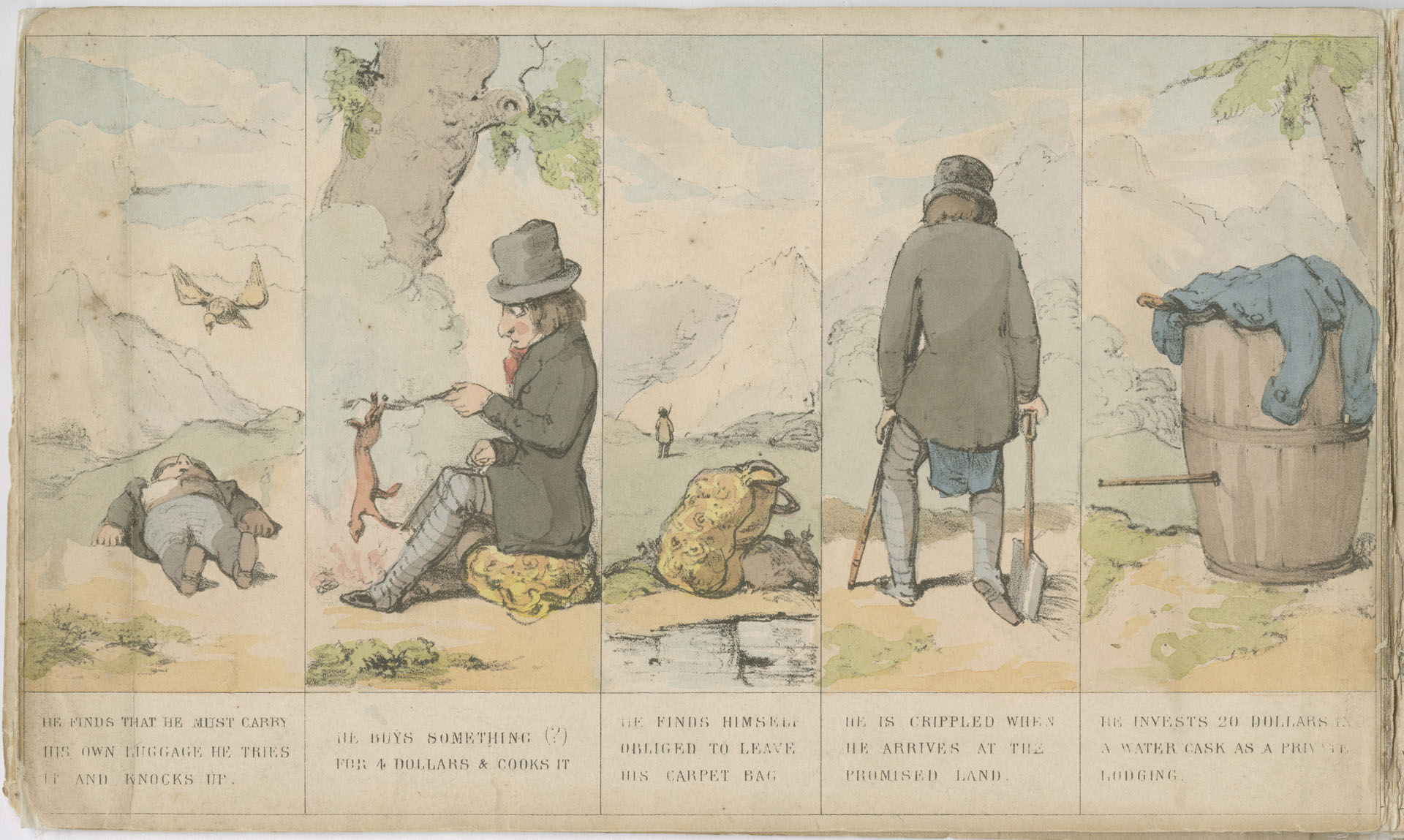

A Good Natured Hint About California, 1849

This satirical English publication by Alfred Crowquill, through a series of cartoon-like scenes, chronicles an unsuccessful trip by main character “Mivins” to the gold fields, his inevitable trials and tribulations, and his joyous return home. Many who came to mine were never successful and chose not to stay in California.

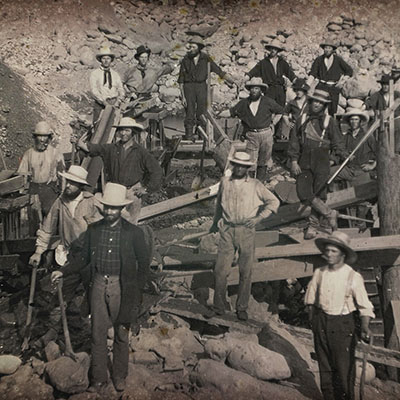

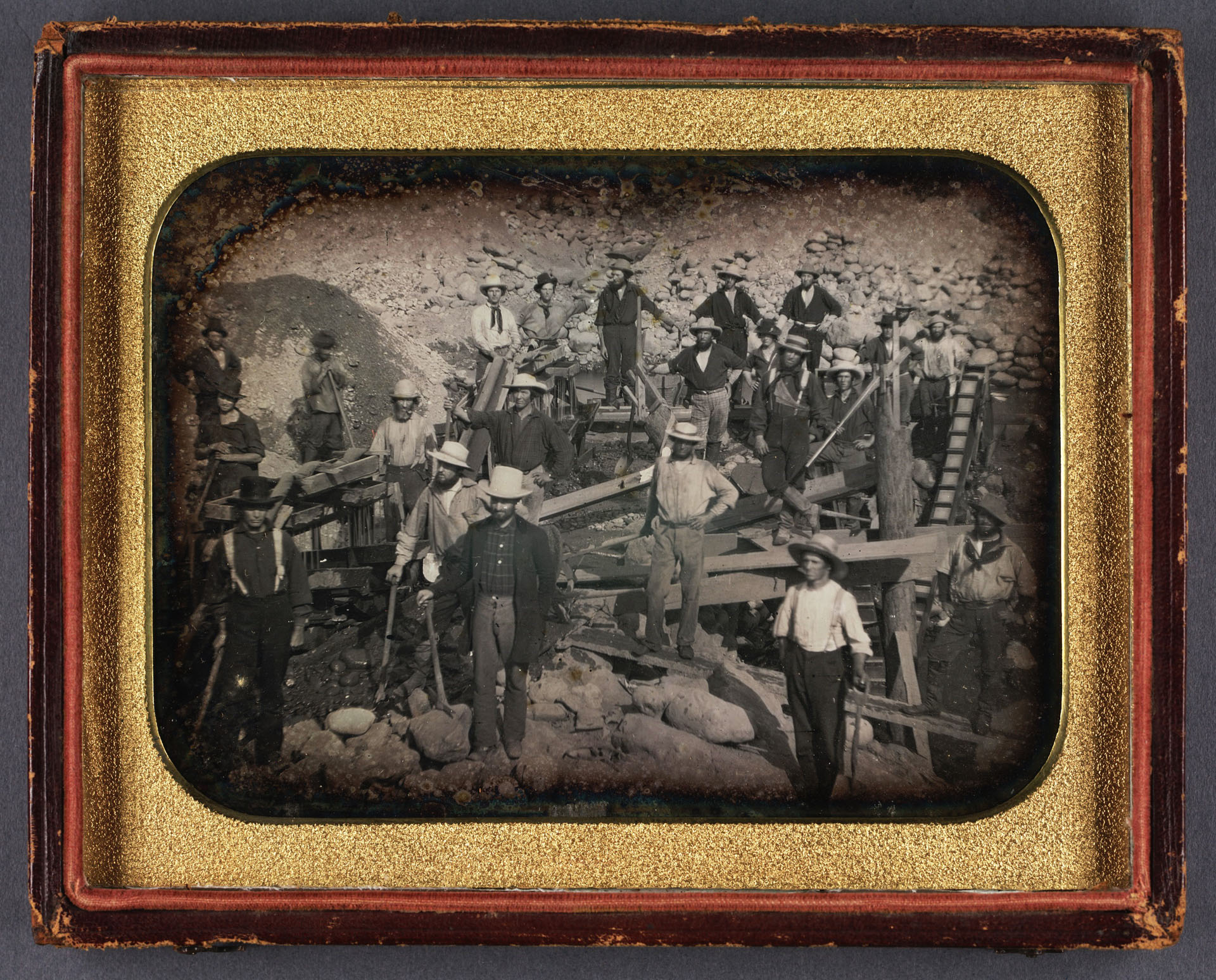

Portrait of 23 miners, ca. 1852

This daguerreotype shows a group of gold miners posed with shovels next to sluices on a rocky hillside. Many publications of the time romanticized the vision of a single miner working alone, but mining was intensive work and more often involved multiple people working together to process enough rock and gravel to make mining profitable.

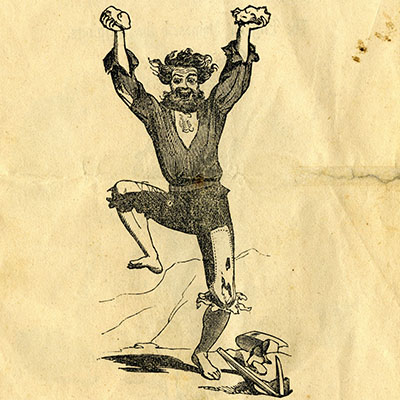

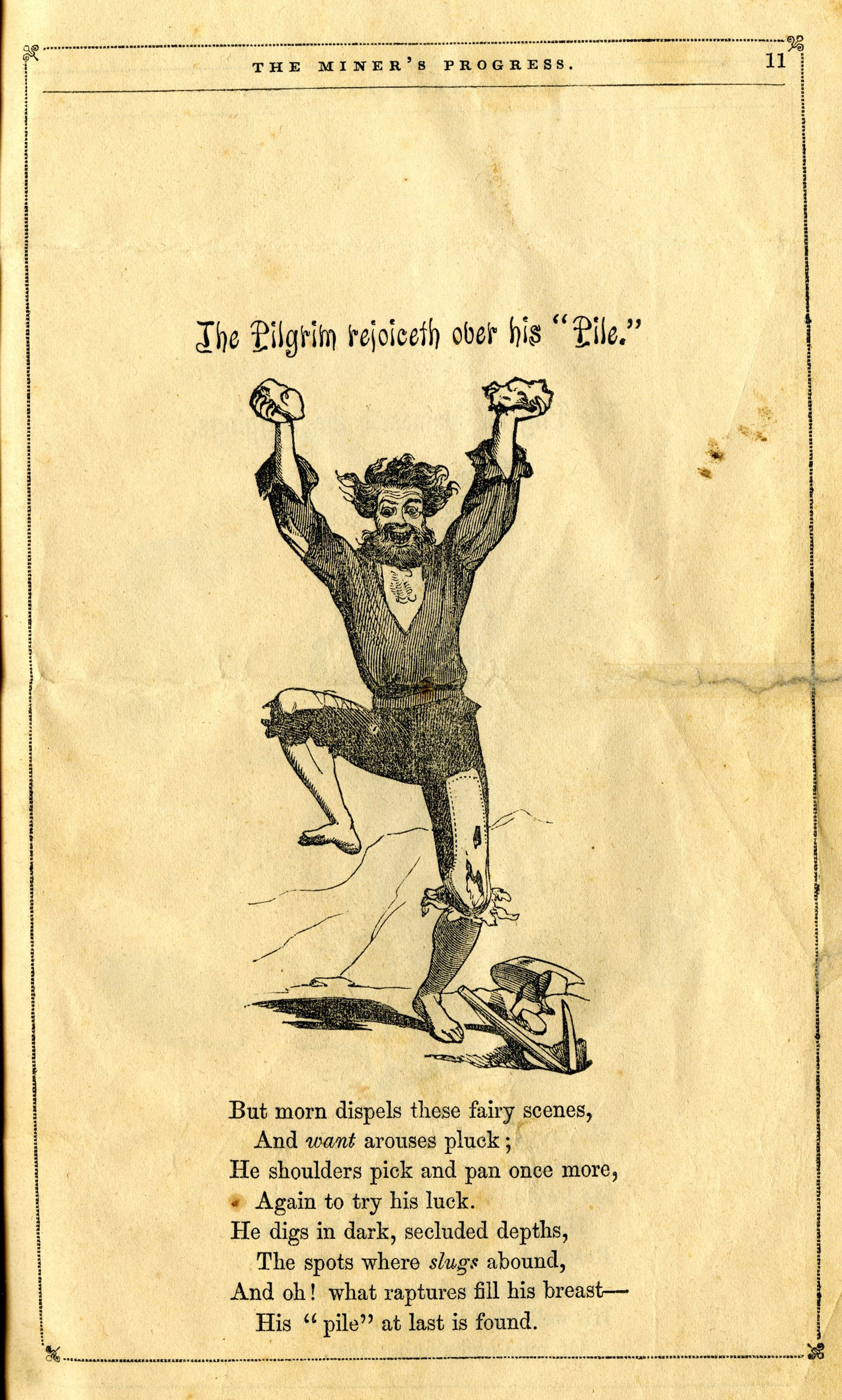

Miners Progress

This illustration was originally published in The Miner’s Progress, or Scenes in the Life of a California Miner in 1853. The image features a romanticized caricature of the single miner, working alone, and then eventually striking it rich.

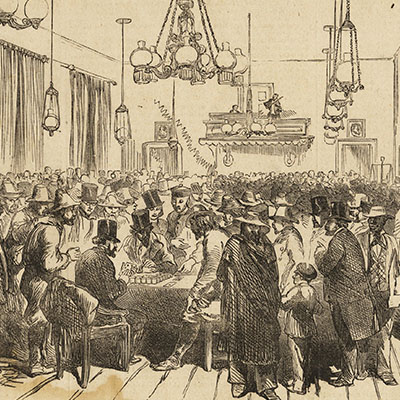

El Dorado Saloon

This is an artist’s interpretation of a Gold Rush era saloon in Sacramento. Miners worked 12-16 hours a day and saloons where a place miners could go to relax, drink, gamble, and pursue other entertainments. This image is a highly romanticized portrayal of a gold rush saloon. In mining towns, the “saloon” was often plank tables under canvas covers for shade.

Auburn Ravine, 1852

While many early arrivals in California were men, women also found economic stability and success in several industries. Selling supplies and food, running boardinghouses and saloons, and providing services like laundry and sewing were profitable enterprises. This is a rare image of a woman in the gold fields, she is seen carrying a picnic basket, possibly bringing food to the men mining.

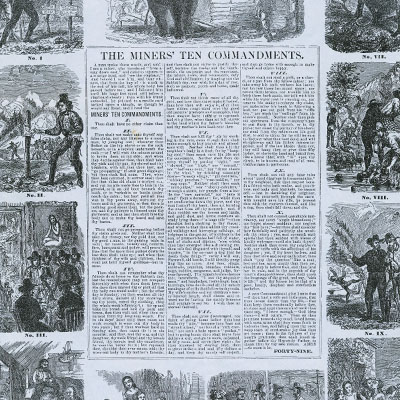

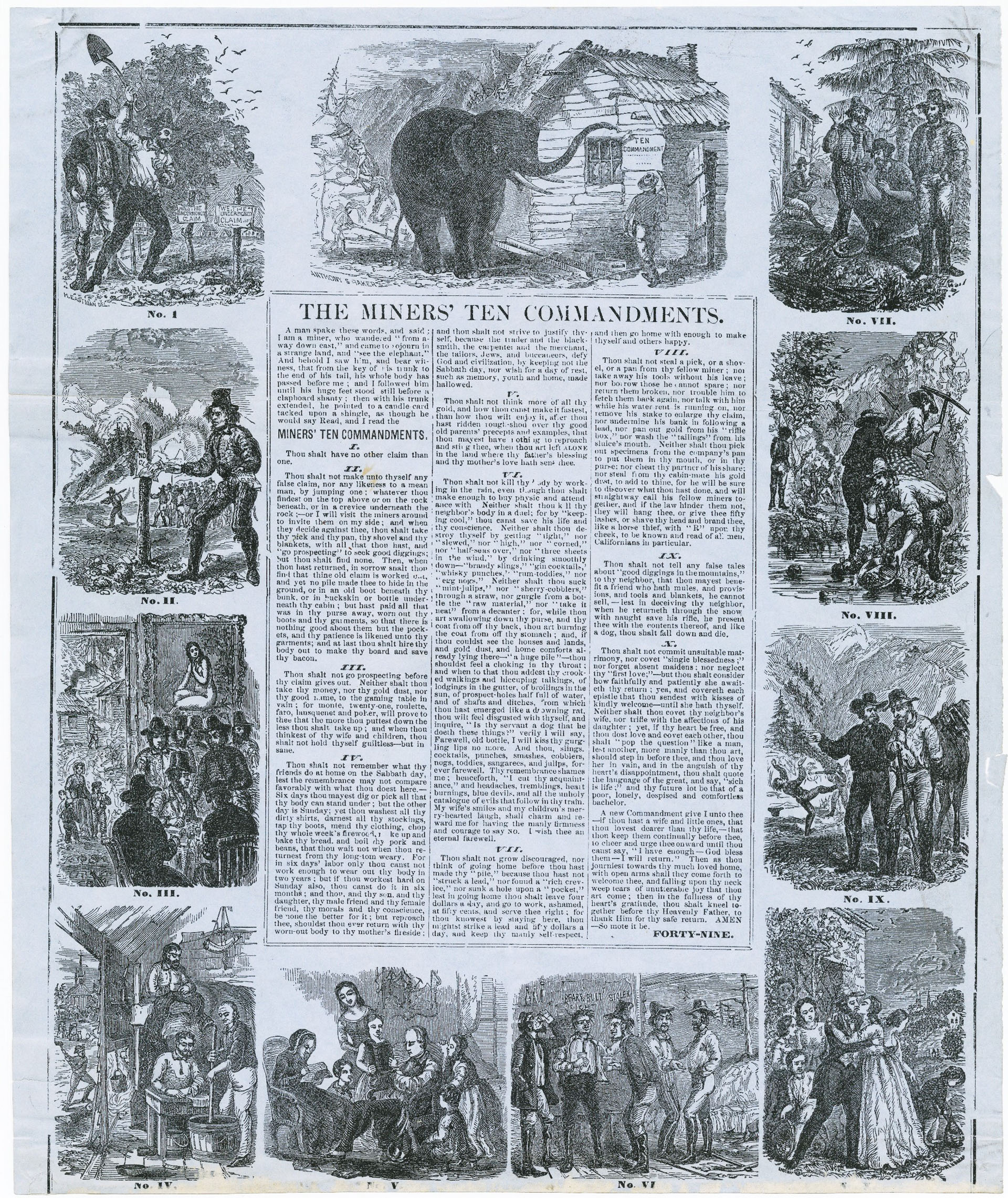

The Miners’ Ten Commandments, 1853

James Mason Hutchings’ letter sheet, “The Ten Commandments” became a veritable best seller yielding sales of close to 100,000 copies. It was printed and reproduced many times over the years due to its humor, memorable parody of the Bible, and beautiful illustrations. Copies were widely shared by miners who would send them home in letters, or as wrapping paper, to friends and family.

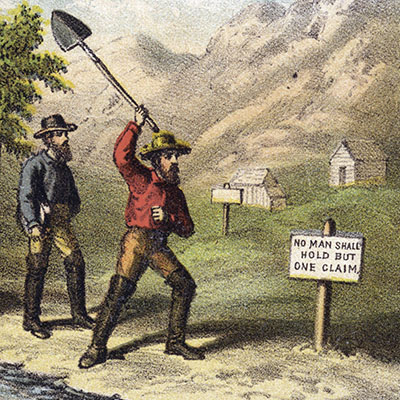

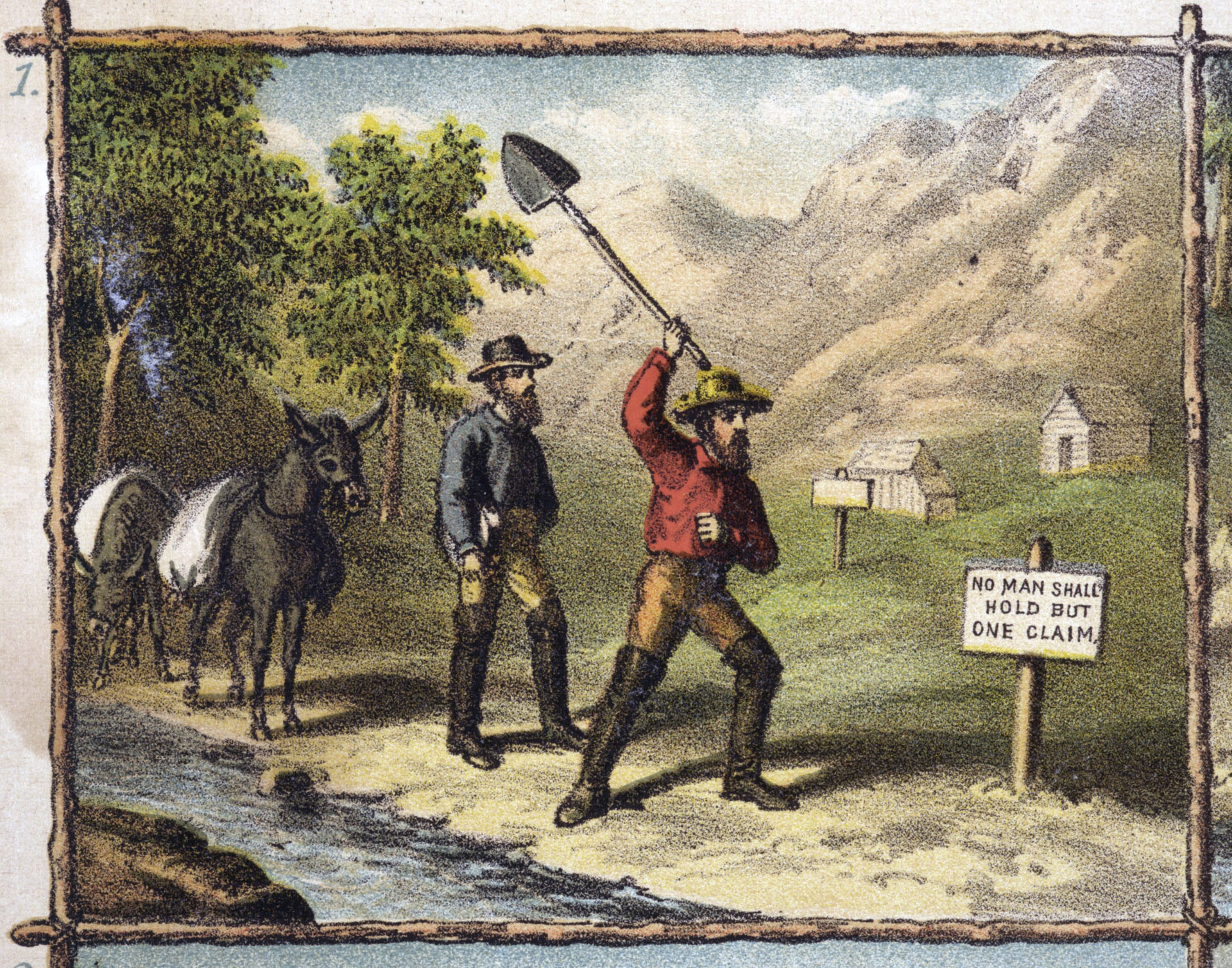

Staking a Claim

This colorful image comes from an 1887 publication of the Miners’ Pioneer Ten Commandments. At the outset of the Gold Rush there was no legal framework in place to govern mining activities, and most miners “staked claims” along streams and riverbeds on public lands, using methods like panning and tools like pickaxes to retrieve gold.

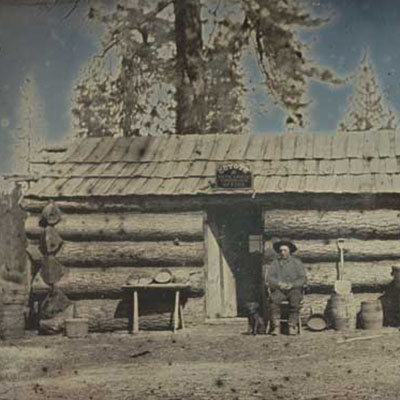

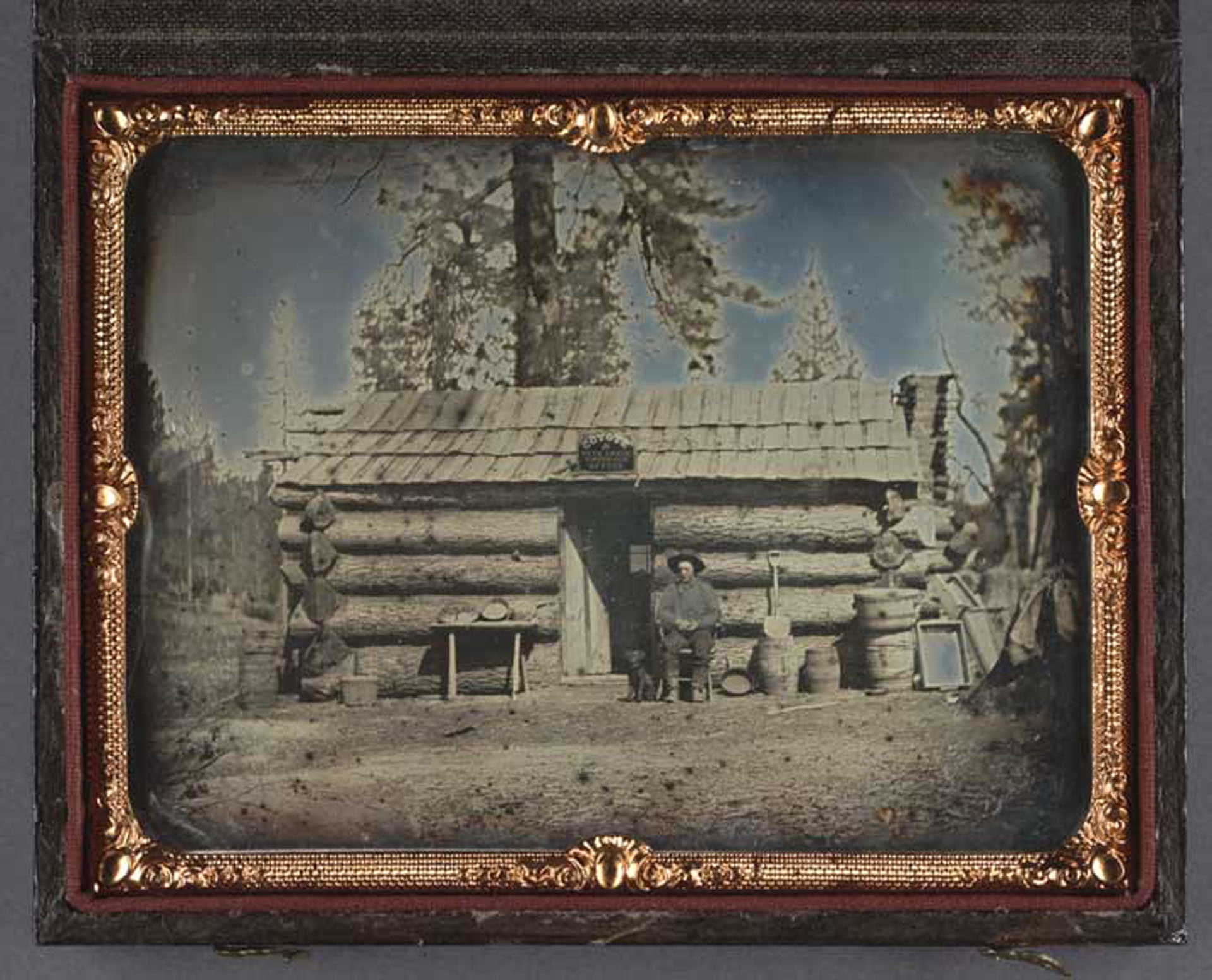

Coyote & Deer Creek Water Co. Office, 1852

This daguerreotype shows a miner and a dog sitting in front of a log cabin with a sign above the door that reads “Coyote & Deer Creek Water Co’s Office.” Mining was both labor and water intensive, so mining companies and water companies were formed. These companies then funded the building of ditches, flumes, and dams to divert water for mining operations. Water would become a contested resource as both mining and farming activities created greater demand.

Near Sugar Loaf Hill, 1852

This daguerreotype shows miners standing near a sluice in front of a log cabin, using tools like a pitchfork and shovel to process gravel. The cabin and sluices indicates that these miners likely stayed and worked this claim for an extended period.

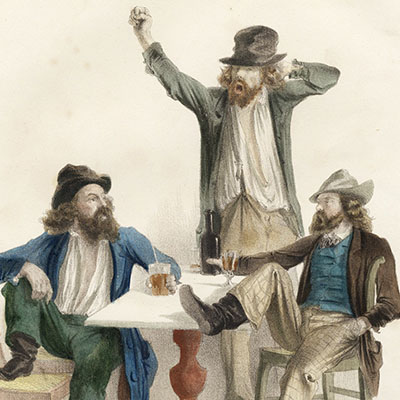

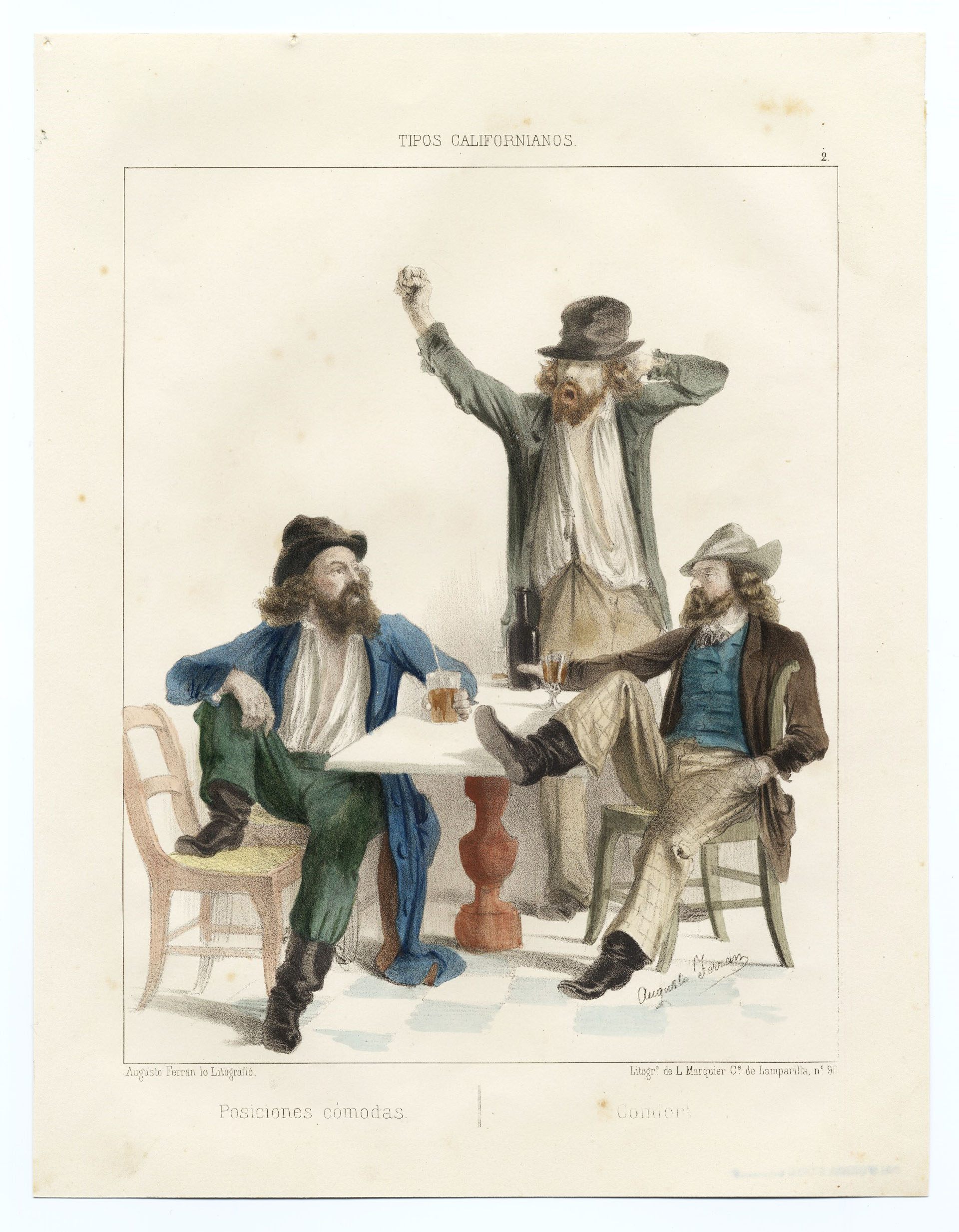

Posiciones comodas, or “Comfort”

In 1849, Cuban artists Augusto Ferran and Jose Baturone traveled to San Francisco to document the Gold Rush. Their series of lithographs portray California gold miners, whom the artists described as Tipos Californianos, or “California Types.” This image shows miners relaxing with drinks.

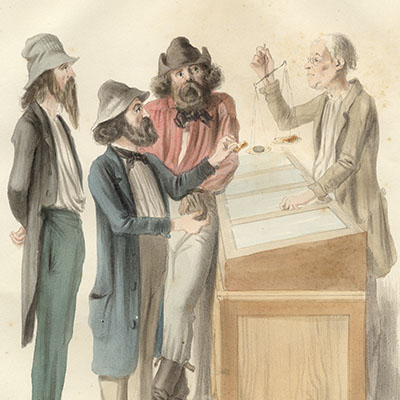

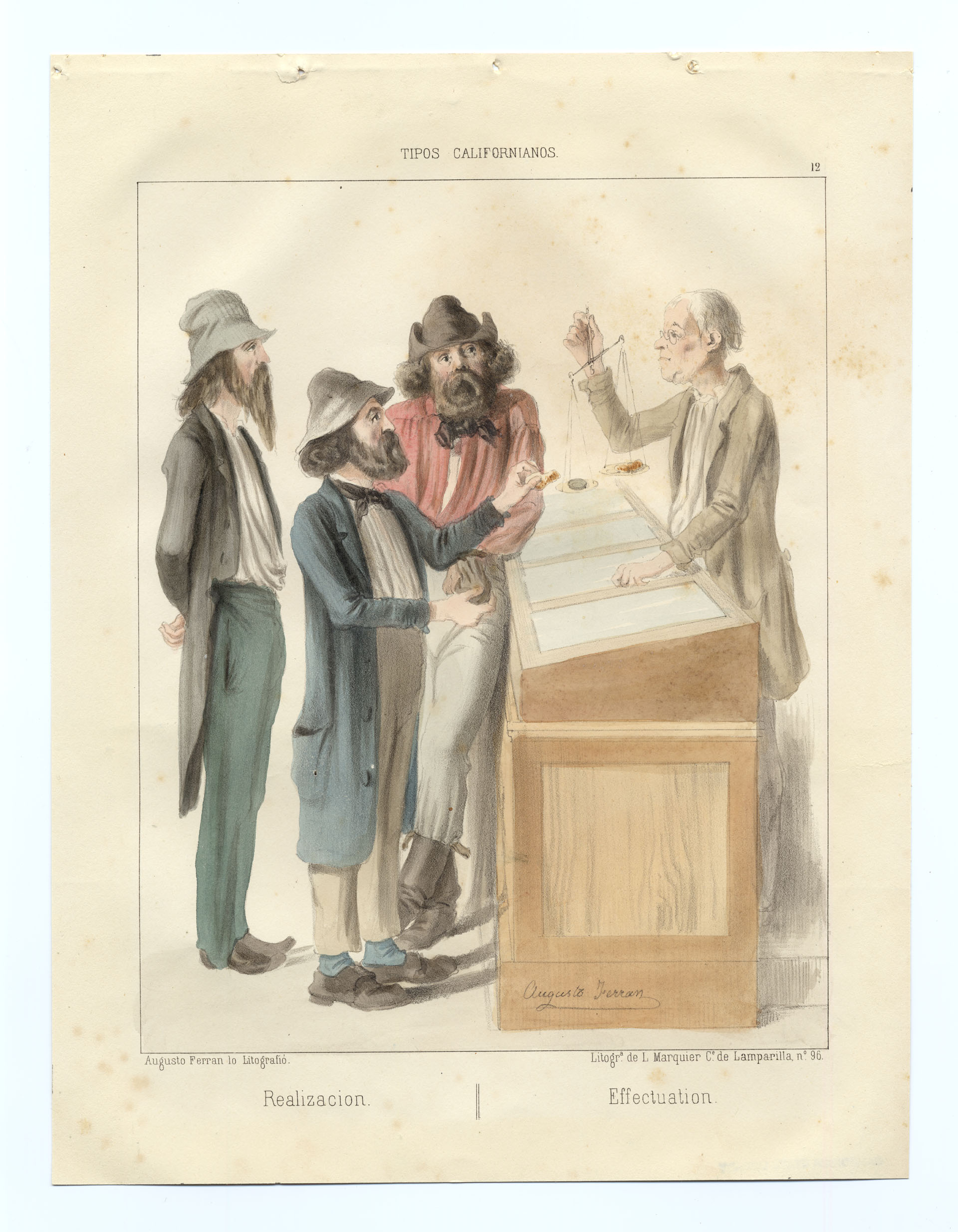

Realizacion, or “Effectuation,”

This colorful image is another example of artists Ferran and Baturone’s work. This image depicts miners taking their gold dust to an assay office, where they would have exchanged their gold for cash.

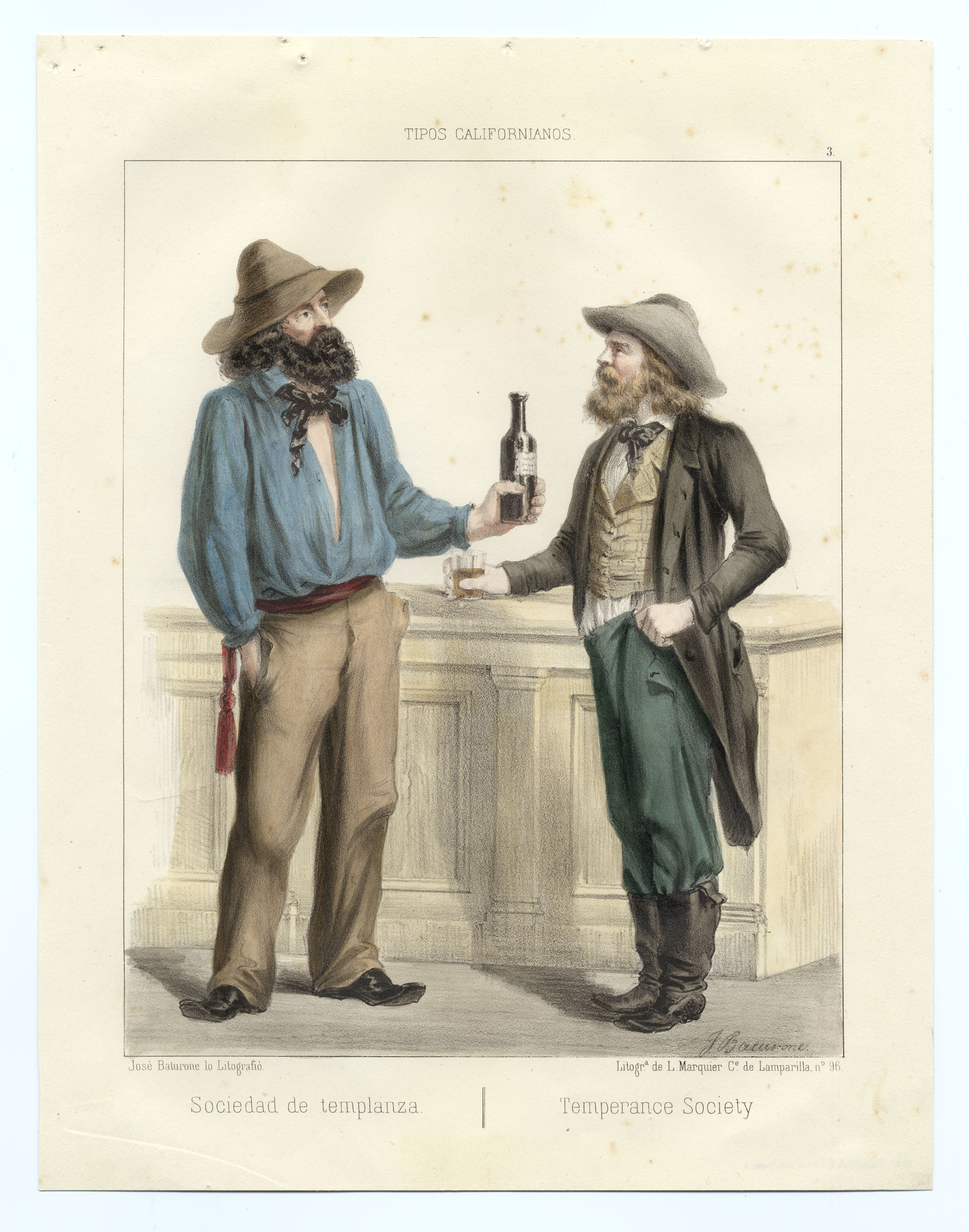

Sociedad de templanza, or “Temperance Society,”

In this image Ferrano and Baturone have some fun by labeling a bar a “temperance society.” The artists are probably mocking the stereotype of the drunk and rowdy gold seeker. Brothels, saloons, and gambling houses were, however, sources of entertainment for miners.

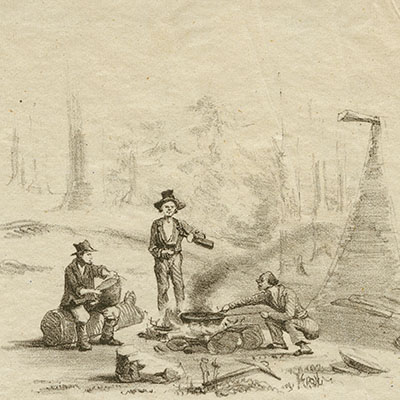

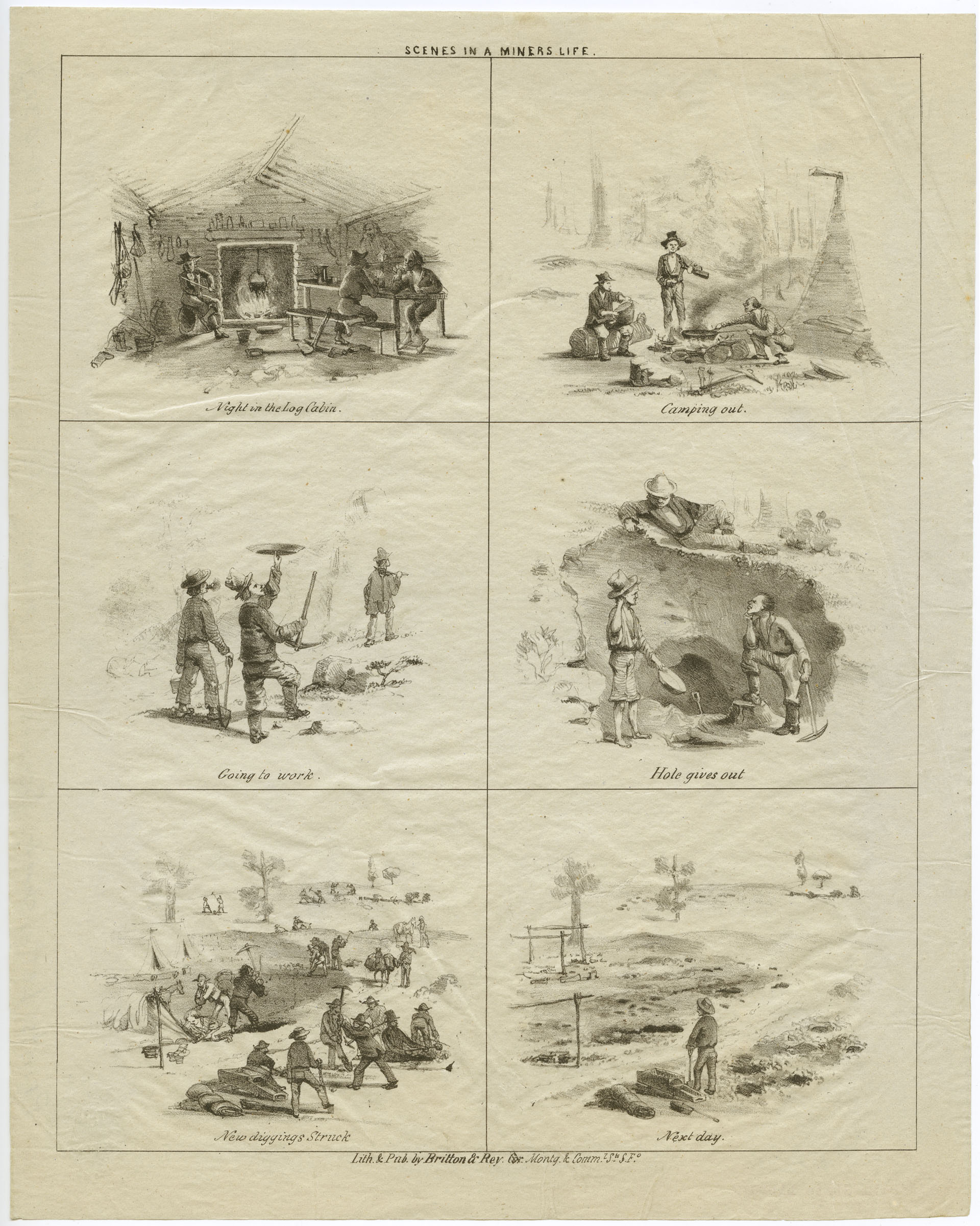

Scenes in a Miner’s Life, 1854

Published in San Francisco by Britton & Rey, this illustration depicts six humorous scenes in the daily life of a California miner. Many miners lived in tents or makeshift cabins in the gold diggings, cooking and washing in their camps and relying on wild game and supplies from the settlements and urban centers that grew expansively as more gold seekers arrived.