Like the architecture, those who worked in the Library and Courts Building and shaped the development of the State Library also inspired ghost stories. It is likely because these figures had such a lasting impact on the State Library and the Library and Courts building that they became the subject of legends and lore. Here are the real stories.

The Librarians

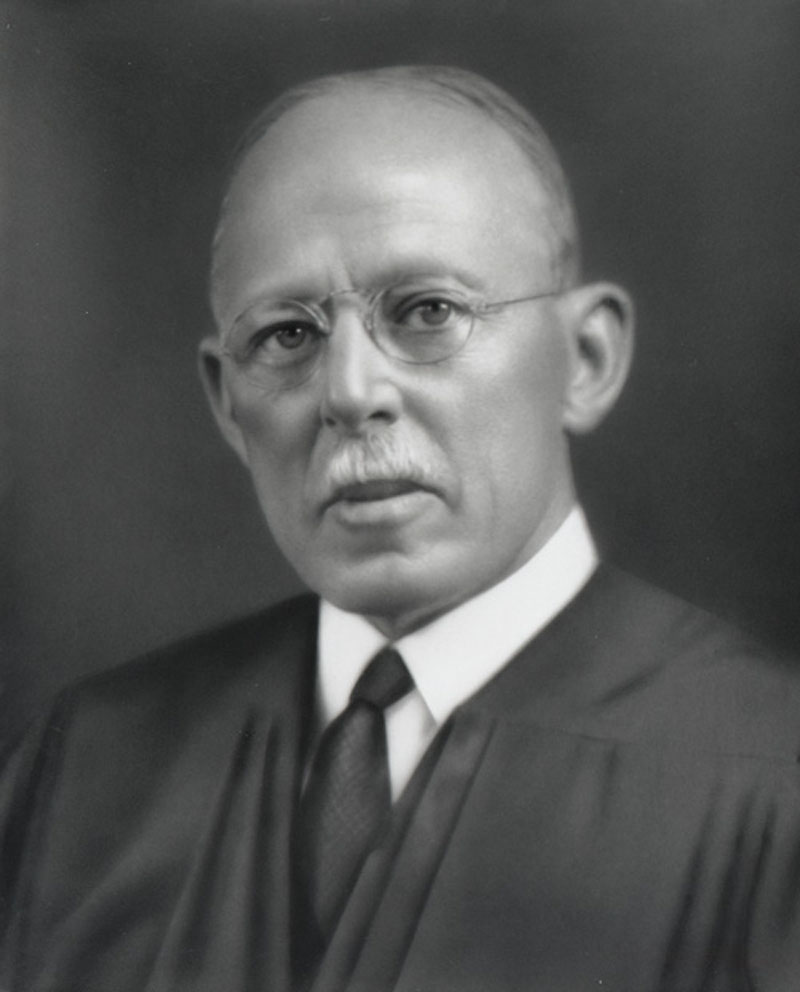

James L. Gillis (1857-1917)

California State Librarian (1899-1917)

James Louis Gillis was the fifteenth California State Librarian. Renowned for organizing library service, innovating new programs, and developing training for librarians, Gillis is perhaps the most consequential State Librarian in California history. Gillis’s list of accomplishments is impressive. He developed the first dictionary system of cataloging for all library materials and began the indexing of all California newspapers. It was during his tenure that a separate Law Library, California Historical Department, and Books for the Blind section were formed. Gillis strongly believed that all Californians should have access to library materials, and it was under his leadership that traveling library services were developed to bring library material to rural Californians. Ultimately, this service was the foundation for the public library system of California today.

Gillis was instrumental in advocating for the construction of the new Library and Courts Building to house the growing library collection. Sadly, Gillis passed away on July 27, 1917, in the Office of the Secretary of State, shortly after arriving for work. Today, the grand Gillis Hall, located on the third floor of the Library and Courts Building, bears a memorial to the beloved State Librarian over the entrance door.

Milton J. Ferguson (1897-1954)

California State Librarian (1917-1930)

Milton J. Ferguson was the sixteenth California State Librarian and the Deputy State Librarian under James L. Gillis. Ferguson’s tenure began in 1917 following Gillis’s sudden death and continued through the completion of the Library and Courts Building project in 1928. Ferguson considered Gillis to be a great mentor and continued in Gillis’s footsteps. As State Librarian, Ferguson was a staunch defender of the California State Library’s position in the construction of the Library and Courts Building. This stance occasionally brought him into conflict with Chief Supreme Court Justice William H. Waste. The two men disagreed on court access through the library stacks: Ferguson did not want court personnel to walk through the library for fear the public would follow, and Waste chafed at the lack of court access.

Ferguson was ultimately successful in diplomatically navigating the construction of the new Library and Courts Building and stayed with the California State Library until 1930. After leaving the State Library, Ferguson served as the Chief Librarian of the Brooklyn Public Library and as the president of the American Library Association from 1938-1939.

Mabel Gillis (1882-1961)

State Librarian (1930-1952)

Mabel Gillis was the seventeenth, and first woman, California State Librarian. Daughter of fifteenth California State Librarian James L. Gillis, Mabel began her career with the library at age twenty-two. Her first position was as assistant in the extension department where she developed programs and services for the visually impaired. She was appointed department head of the Books for the Blind Section when it was formally created in 1911, and appointed Deputy State Librarian in 1917 when her father died and Milton J. Ferguson, then Deputy State Librarian, was appointed State Librarian. As Deputy State Librarian, much of Gillis’s job was to oversee the construction of the Library and Courts Building project. When Ferguson retired in 1930, Gillis was appointed State Librarian, a position she held for twenty-two years.

Mary “Eudora” Garouette (1863-1943)

Librarian

Librarian Mary Eudora Garouette was the Chief of the California Historical Department under State Librarian James L. Gillis. Garouette began her career with the California State Library in 1899 and served as the head of the California Section for thirty-four years. A pioneering woman of her time, Garouette was pivotal in developing the library’s California History collection into the highly regarded resource it is today.

The Judges

Elijah Carson Hart (1857-1929)

Associate Justice of the District Court of Appeal, Third District

Elijah Carson Hart was a distinguished lawyer, Sacramento City Attorney, Assemblyman, Senator, and highly regarded jurist. Judge Hart served for twenty-two years as Associate Justice of the District Court of Appeal, Third District. Prior to entering law, Hart was a journalist and owned his own newspaper.

Perhaps the most persistent rumor of a haunting states that Third Appellate Court Justice, Judge Elijah Carson Hart passed away in his chambers of the Library and Courts building, and that he consequently haunts the library. Although Judge Hart was found unresponsive in his chambers by his son Cavins, he was rushed to the hospital where he tragically passed away in the early hours of January 18, 1929.

William H. Waste (1868-1940)

21st Chief Justice of California

Supreme Court Justice William H. Waste was the twenty-first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of California. Waste was the last of four successive Supreme Court Justices to serve on the Sacramento State Buildings Commission during the construction of the Library and Courts building. Waste attended his first State Buildings Commission meeting on June 11, 1926. During this meeting, Waste and the California Supreme Court proclaimed their intent to continue holding court in San Francisco. This proclamation defied California’s Constitutional Mandate that all state officers and offices be located in the Capitol. The court claimed they would occasionally take up residence in the nearly complete courtroom on the fifth floor but relinquished many offices.

On December 12, 1927, Justice Waste made what was viewed as a shocking demand. The elaborately constructed courtroom was almost ready when Waste refused to conduct court business on the fifth floor. He believed the space to be unacceptable and wanted the court moved to the first floor. On January 17, 1928, the Commissioners ordered architect Charles P. Weeks to re-create the finished fifth floor courtroom on the first floor in every detail. This drastic change was costly and caused conflict between the courts and library. During their tenures, Justice Waste and State Librarian Milton J. Ferguson battled over first floor court access through the library with neither side willing to concede.

The Architects

Charles Peter Weeks (1870-1928)

Architect

Charles Peter Weeks was an acclaimed architectural designer. Weeks, along with William Peyton Day, architectural engineer, formed the firm of Weeks & Day in 1916. Weeks & Day specialized in the architectural design and construction of theaters, hotels, and luxury apartment complexes. The firm is responsible for many iconic California buildings including the Mark Hopkins and Sir Francis Drake hotels, the San Francisco Chronicle building, the Fox Theater in Oakland, and the Lowes Theater in Los Angeles.

Weeks & Day signed the contract to design the two new buildings of the Capitol Extension on November 30, 1918. Weeks was particularly invested in the construction of the Library and Courts building and designed many of the grand chandeliers located throughout. Weeks personally chose his sculptor friend, Edward Field Sanford, Jr., to design and complete the massive sculptures seen today on the pediments of the buildings.

Weeks’s health was already declining when conflicts around space allocation arose between the courts and library in 1926. Chief Supreme Court Justice William H. Waste demanded that the elaborately constructed fifth floor court chambers be moved to the first floor of the building. The stress of this move is believed to have exasperated Weeks’s frail condition. Sadly, before ever seeing the fruits of his labor, Weeks passed away from acute heart dilation on March 25, 1928.

An interesting note: Weeks’s widow, Beatrice Woodruff, married actor Bela Lugosi a year and a half after Weeks’s death. The marriage lasted four days, and the divorce was final within a year. After the divorce, Woodruff returned to using Weeks as her last name.

George B. Mc Dougall (1868-1957)

California State Architect (1913-1928)

George Barnett McDougall was the California State Architect who oversaw the construction of the Capitol Extension Project. McDougall was appointed California State Architect in 1913. He was one of only two members of the Sacramento Buildings Commission that were present on the project from inception to completion. McDougall came from a family of distinguished architects. His father and brothers were all noted architects who had firms in Fresno and San Francisco. McDougall skillfully navigated many funding crises and personality conflicts during the construction of the new buildings. The completed buildings were admired from coast to coast for their stately architecture and elaborate artwork.

The Artist

Edward Field Sanford, Jr. (1886-1951)

Monument Sculptor

Edward Field Sanford, Jr. was a relatively unknown sculptor of monuments and a friend of Charles P. Weeks, architectural designer of the buildings. Sanford was commissioned to design two pediments, four large statues, and twenty-four panels for the two new buildings of the Capitol Extension. His work was applauded for its size and scope; however, the Sacramento State Building Commission was not entirely pleased with his designs and required him to make revisions. Ultimately, Sanford did not complete the twenty-four panels but he did complete the pediments and four large statues that flank the entrance doors of the buildings today. Sanford additionally created two magnificent bronze statues, “Wisdom” and “Inspiration,” that are displayed in the old Circulation Room across from Gillis Hall on the third floor of the Library and Courts building.

Sanford’s affection for Weeks is evident in his written correspondence. In a letter dated June 6, 1927, Sanford thanks Weeks for advocating for his work and continued support during his negotiations with the commissioners. In that same letter, Sanford refers to Weeks’s lingering health problems and wishes him a full and speedy recovery. It would be less than a year later, in March of 1928, that Weeks would succumb to those same health issues before the completion of the project. Sanford considered the sculptures that he created for the Capitol Extension to be his crowning glory.