About Sutro Library

I must confess that of all the amazing things on the Pacific Coast — and I encountered surprise after surprise — the most unexpected was the discovery of the Sutro Library, and of the fact that so few people in California knew anything about it.

Editor, Christian Advocate, 1892

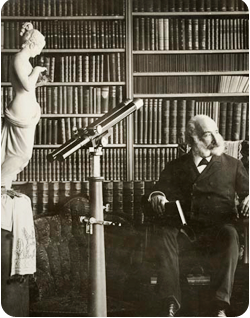

The Sutro Library is the legacy collection of former San Francisco mayor, engineer, entrepreneur, and philanthropist Adolph Sutro (1830–1898) and is located on the campus of San Francisco State University. This special collection and educational research institution has over 125,000 rare books, antiquarian maps, and archival collections, as well as the largest genealogical library west of Salt Lake City. It was deeded to the California State Library in 1913 by Sutro’s heirs and opened to the public in 1917. It was also the only library in San Francisco to survive the “Great Fire” after the 1906 earthquake.

Early Beginnings

Adolph Sutro came to San Francisco from Prussia in 1850 at the height of the Gold Rush. He made his money as a mining engineer in Virginia City, Nevada — where the famous Comstock Lode was discovered. Ever civic-minded, Sutro wanted to improve San Francisco’s the quality of life and provide its citizens a world-renowned research collection without equal.

To this end, Sutro began collecting items for his library in late 1870s and by the time of his death in 1898 had amassed a collection of 300,000 to 500,000 rare books including 4,000 incunabula (the first books printed in Europe using a printing press), which according to contemporary news accounts was the seventh largest library in the world. Sutro realized the magnitude of building a research collection that would cover almost every subject so he hired German and British experts to go to auctions and other book sales to make acquisitions. Sutro died on August 8, 1898, with his heirs deeding his library to the California State Library in 1913, and officially opening to the public in 1917.

The Wandering Library

The Sutro Library has moved several times in its hundred-plus year history. In 1895, after negotiations with the University Regents, Adolph Sutro’s personal and much prized collection of antiquarian books, maps, and archives (300,000 to 500,000) was to be donated to the “Affiliated Colleges” of the University of California in San Francisco.1 In 1895, the State Legislature appropriated $250,000 to establish colleges in San Francisco to teach medicine, veterinary science, dentistry, pharmacy and law. The land for the university was donated by Adolph Sutro, with the condition that a site for the library would be housed adjacent to the Affiliated Colleges’ buildings.2

The same year as negotiations with the Regents were taking place Sutro became mayor of San Francisco, diverting his attention to politics. That, coupled with his declining health, prevented him from erecting a building to house the library. The April 17, 1896 edition of the Sacramento Daily Union noted that Sutro had still not followed through on his promise to donate his library. When he passed away in 1898, the collection remained in limbo, housed in two warehouses in downtown San Francisco — one on the Montgomery block and the other on Battery Street.

Immediately following his death, claims about the validity of the will made headlines. The University of California Regents felt that the library should be given to the colleges as had been Sutro’s intent, both reported upon in newspapers, and in writing by him. There were also questions as to why Sutro, whose estate had grown exponentially in the previous decades, had not amended his 1882 will. A fact that, according to the San Francisco Call, resulted in over half of the beneficiaries named in the will were no longer alive. Additionally, a woman came forward named Mrs. Kruge claiming paternity of her two children belonged to Sutro and that she firmly believed Sutro would have provided for her and her children.3

In 1902, Kruge settled for $100,000 and after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake (which contemporary sources estimated two thirds of Sutro’s collections burned), the family settled the matter of the library. At the urging of Sutro’s daughter and executor of the will, Emma Merritt, the family donated Sutro’s collection to the State Library with the stipulation it never leave San Francisco – as Sutro had always intended it to be a world renowned library helping to make San Francisco a modern urban center.4

In 1913, the California State Assembly accepted and passed a bill to put Sutro library under the stewardship of the California State Library:

The bill is as follows: An Act authorizing the trustees of the State library to accept as a gift from the heirs of the late Adolph Sutro of the city and county of San Francisco, the library commonly denominated the “Sutro Library,” and to establish a branch of the State library in the city and county of San Francisco and making an appropriation for the establishment and maintenance of the same. The people of the State of California do enact as follows: Section 1. The trustees of the State library are hereby authorized to accept as a gift from the heirs of the late Adolph Sutro in accordance with the terms and conditions thereof, on behalf of the State of California, the Sutro collection of rare books and manuscripts gathered by the said Adolph Sutro, in his lifetime, consisting of about 125,000 volumes and estimated to have a valuation of more than one million dollars ($1,000,000.00}. Section 2. This collection of books in accordance with the terms of the gift shall be maintained In the city and county of San Francisco as a branch of the State library, which branch the trustees of the State library are hereby authorized to establish, and shall be known as the “Sutro library.” Subject to the terms of the gift, the library shall be under the direction and management of the board of State library trustees. Section 3. There Is hereby appropriated out of any monies in the State treasury not otherwise appropriated the sum of seventy thousand dollars, for the purpose of equipping and maintaining said library, of which the sun. of fifty thousand dollars shall become available during the sixty-fifth fiscal year and the sum of twenty thousand dollars shall become available during the sixty-sixth fiscal year.5

Sutro Library finally opened to the public in 1917 in the Lane-Stanford Medical School and Library building, located at Sacramento and Webster streets in San Francisco. That same year the California Genealogical Society’s collection joined the Sutro Library under a loan agreement, making state library staff responsible for supervision and circulation of their collection as well.6

As ‘Lane’ was meant to serve only as a temporary headquarters, it was a matter of some urgency to find a more central location for the library in San Francisco. The State Librarian wanted to make sure library services would be “free to all and should be equally accessible to all,” which meant near public transportation. He also wanted to make available, through Sutro, the entirety of the California State Library’s collections in Sacramento. 7

In 1923, Lane Medical Library needed more space and so the Sutro Library moved to the San Francisco Public Library at Civic Center. While the California Genealogical Society continued to meet annually at Sutro, in 1933 they moved their collection to the California Society: Sons of the American Revolution located in San Francisco. Sutro Library was given space in the public library’s reference room, but there wasn’t proper storage space for the rare books.

Dissatisfaction over the cost to run the Sutro library coupled with the perception that Sutro library was not operating to “the agreed to conditions….which the State of California has failed to perform and which it is not practicable nor feasible for the State to perform…” put the future of Sutro’s existence in peril.8

In 1933 three bills were introduced to the State Legislature by Senators Hays, Bush, Engels, Moran, Allen, Duval and Swing. While two of the bills sought to return the collection to Sutro’s heirs, the third proposed to move Sutro Library to Sacramento.9 San Franciscans as a community came together to protest. Prominent Bay Area citizens wrote impassioned articles arguing about the cultural and educational importance of Sutro Library. Printer John Henry Nash wrote: “Libraries, art galleries and museums are properties that make cities great and interesting.”10 None of the bills passed.

San Francisco Public Library needed the space the Sutro Library occupied causing yet another move for collection. In 1957 the State Library assembled a committee to evaluate the collection, its needs, and to find a suitable location.11 In 1959 Glenn Dumke, President of what was then San Francisco State College (San Francisco State University (SFSU)), renewed a previous offer to house the Sutro Library on the campus.12 The University of San Francisco (USF), a private Jesuit university, offered to house the Sutro in their Gleason Library that same year.13 The State Library accepted the latter offer and signed a 20 year lease on January 1, 1960. As part of the final agreement, the Sutro Library would be open and accessible to the public, would have to build a separate entrance, and would pay $1.00 per year in rent. 14

By the early 1980s, USF let the State Library know that they intended to reclaim the space Sutro occupied at Gleason library.15 In 1983 Sutro Library moved into a building on land owned by SFSU at 480 Winston Drive behind the main campus. The building SFSU provided for Sutro Library was the former temporary chambers for the California State Legislature during its restoration. The modular prefabricated building was shipped to Winston Dr. and constructed on site. It opened to the public March 1, 1983. It was, however, not an ideal home for the library, as it lacked the amenities that rare book storage needs.

In 2002, Governor Gray Davis’ Economic Stimulus Package was passed and included funding for a permanent home for the Sutro Library in a joint-use facility. The new facilities were in the renovated J. Paul Leonard library and included seismic retrofitting, a Library Retrieval System, space for Sutro Library and the Labor Archives, and climate controlled storage. Finally in 2012 the Sutro Library moved into its permanent home on the fifth and sixth floors of the J. Paul Leonard Library — Sutro Library. 16